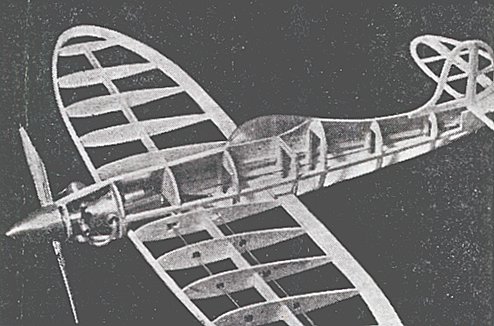

A part sectioned "Marlin" showing the internal structure. The power unit is a 1.8 c.c. Elfin diesel.,

There have been tremendous changes in control line design during the winter months, and our ideas are very different now from what they were at the end of last season.

Stunt and speed flying have progressed considerably, the former probably more than the latter, and the stalwarts who have been practising assiduously through the cold winter weekends are going to reap their just reward in the coming contests this year.

Seeing the models being currently flown through stunt schedules, one immediately notices two things: the great advance in technique and the smooth confidence with which the experts tackle stunts not even attempted last year; and the very great difference in design and construction of machines since last year.

In fact, these two things are related. The advance in stunt technique undoubtedly owes a lot to advance in design, and the two may be summarised by saying that the contest winner this year will have to adopt a system of high speed stunting with a machine designed to do this.

Last year most of our experts were flying ugly models with slab-sided or profile type fuselages, and parallel chord wings. Elevators were in most cases as large as they could be, and desperate efforts were made to obtain as much up and ddwn movemeent as possible. Based on our knowledge at that time the general idea was to get at least 45 deg. of up and down movement, and machines all too often mushed out of manoeuvres in which the application of such excessive control movement caused a partial stall. Towards the end of the season it was already obvious that such excessive control was most undesirable and the experts were already "flying" through afl their manoeuvres without using the full range of available devator movement.

Now this effect is even more noticeable. There are successful machines being flown every weekend at Fairlop with only 15 deg. of up and down elevator movement and careful observation shows that in performing high speed loops, bunts and figure-of-eights only a part of even this small movement is being used. Full movement is reserved for emergencies only.

Of course, the machines used to fly in this manner are different in many ways.

Firstly, wing loadings are much lower. That means that for an engine of a given weight, which generally means for an engine of a given capacity, a much larger wing area is being used. The Elfin 1.8, probably the most popular stunt diesel at the moment, weighs only 3.5 oz. and is used in models of about 200 sq. in. with an all up weight of as little as 9.5 oz. It is, in fact, the same wing loading as a heavy Wakefield model - which makes you think, doesn't it?

A typical successful model of this type is that at present being flown by Dennis Allen and some other members of the West Essex Club. This is very much like a Spitfire in appearance, is fully streamlined with a monocoque fuselage, and has elliptical wing and tail surfaces.

The elevator is less than 50 per cent. of the tail area, and the movement about plus and minus 20 deg.

Construction is by the crutch method and the photograph on this page of the part-sectional model again shows how light is the internal structure.

With an 8 x 6 propeller this model is definitely fast, speeds up to 65 m.p.h. being easily attained on 45 ft. lines.

A part sectioned "Marlin" showing the internal structure. The power unit is a 1.8 c.c. Elfin diesel.,

At this speed on these lines stunting is fast, and one has not a lot of time to spare in thinking what one is going to do next. It is, therefore, no model for a trainee. But in the hands of an expert it goes smoothly through all the stunt schedule including vertical and overhead figure-of-eights.

No model last year, even fitted with a 10 c.c. petrol engine would have done so well.

The contributory factors to the model's efficiency, are its light weight and loading, clean aerodynamic layout, ability to fly fast, and last, but by no means least, the increased technique of the pilot.

As long as the weather conditions are fair (for these light machines will always be at a disadvantage in high winds) a machine of this type is quite capable of winning the Gold Trophy this year.

At the other end of the stunt scale, machines with big engines are still being built and the tendency in the really "hot" designs is towards the short-coupled lightly loaded high-speed job which follows the lightweight except that the moment arms are getting shorter and shorter.

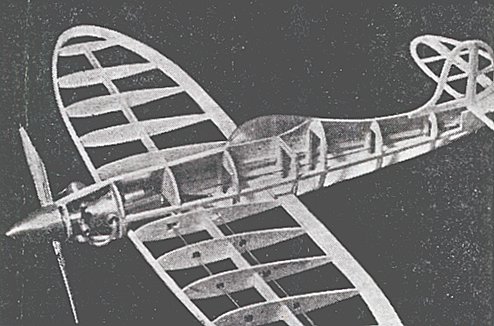

One of the photographs on this page, is of the author's latest effort which is fitted with an Anderson Spitfire. Span is 56 in. and the area about 650 sq. in.

The author's latest model, the "Monitor" powered by an Anderson "Spitfire". For further details see text.

(Recent information suggests that Ron Moulton built this model. Ron reports that it flew like a pig and was impossible to hand launch - DD).

It stunts at around 80 and using as little as 10 deg. elevator movement can perform all the manoeuvres in the full stunt schedule.

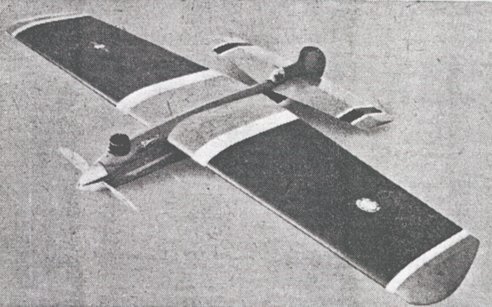

The general layout is not dissimilar to de Bolt's new design, the Stunt-wagon (see photograph), but the construction is entirely different, and the model is much lighter despite the fact that the Stunt-wagon is meant for glow-plug whereas the Anderson is running on normal spark ignition.

Harold de Bolt's "Stuntwagon". Wing span: 58 in.: Wing raea: 667 sq.in.: Weight: 48 oz. Power unit: Atwood "Glo-Devil". Highest speed: 102 m.p.h. Gliding speed: 15 m.p.h. Will do 20 laps with a dead engine from the top of the circle. The answer to high speed stunting.

Interesting thing is that the Anderson job has no offset on the fin or the motor yet it pulls like a tractor on 65 or 70 ft. lines.

The adoption of the outside wing weight, which is now standard practice amongst the boys who know, may have a lot to do with this. The idea is to balance the dead weight of the lines which tend to pull down the inside wing and bank the model into the circle. As soon as this happens a part of the wing lift will tend to slacken off the line tension and control will be partially lost. Eventually if the inside wing drops enough the model will free flight into the circle. This has happened to all of us at least twice!

With a correctly balanced wing tip weight in the outboard wing, however, this tendency is overcome and the model will keep under control throughout the most complicated flight patterns. What is more, this balance weight is equally effective in the inverted position.

To one who has never flown a model balanced in this way, the first experience of it is really amazing. Johnny Nunn, Canadian control-line flier of the Barking Club, told me that he considered it the greatest advance in stunt model layout so far. Try it yourself if you have not already done so and see just how well worth while it is.

A smaller version of the Anderson job is now being built for the new Amco 3.5 which promises to be a really fine stunt and speed motor. I have had two of the prototypes on test for weeks now and they do a genuine 12,000 r.p.m., which is fast for any motor, and extremely so for a diesel. On my own test bed a figure of 0.18 b.h.p. has been recorded and when one considers that the motor weight is 4 oz. it should be the last word in diesels for control-line work.

Area for the Amco job is 300 sq. in. the model being almost exactly scaled down from the big one.

Another trend to be welcomed in stunt design is the really scale model. It is, of course, much more difficult to stunt a real scale job than a semi-scale one, and if Allen's job was converted into a true Spitfire with scale tail surfaces and all the trimmings its performance would certainly suffer.

But the Veron" Sea Fury" is an example of what can be done in this direction, and although I have not seen one fly, I have heard very good reports as to its pefformance when properly built and flown.

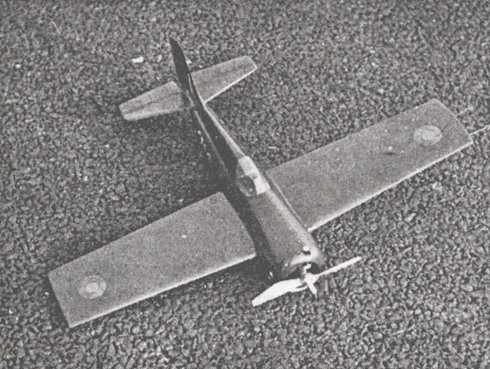

At Fairlop recently two West Essex members, Ron Norris and Ken Oliver had a nice looking "Martlet" with an Elfin which looped but did no more. Area was 180 sq. in. and all-up weight 13.5 oz. It seemed to be definitely underpowered and they are now busy revising the layout to take the new Amco as soon as one is available. This promises well and it should make a nice model. It is rather like the de Bolt "Wildcat" but that is inevitable as the prototypes were related anyway. (See picture below.)

An Elfin powered "Martlet" by Ron Norris and Ken Oliver, of the West Essex Aeromodellers.

Incidentally all the stunt machines mentioned above are flown without undercaniages, the lightweights being hand launched and the heavyweights using drop-out undercarriages.

Final note; there is a rumour that already the S.M.A.E. are considering the advisability of altering the Gold Trophy for the 1950 Nationals to something more interesting than purely stunt.